Shelly Sinclair, shsinclair@davidson.edu

This web page was produced as an assignment for an undergraduate course at Davidson College.

Click here to visit our homepage.

The population history and genetics of prehistoric dogs mimics that of humans indicating that the two groups possibly migrated alongside one another and that there are recurring evolutionary population dynamics for different species.

The origin of domesticated dogs is frequently studied and has shown many contradictory findings over the last few decades. There has been debate over the temporal origin of domestic dogs occurring with either a single starting point (Bergström et al. 2020) or a dual starting point (Frantz et al. 2016) in evolutionary history. Further, there is a debate over the geographic origin of domestic dogs that suggest Europe (Thalmann et al. 2013) or East Asia (Savolainen et al. 2002) as the starting point. Additionally, research on prehistoric dog genomes has shown that wolves and dogs evolved from a common ancestor (Fig.1) and that there is a possibility that wolves were the first to be domesticated. (Khlopachev and Sablin 2002). DNA analyses have confirmed that wolves and dogs share a common ancestor and this idea is supported uniformly from different researchers. However, DNA analyses and genomes analyzed have been used to corroborate the conflicting hypotheses on the temporal and geographic origins. These conflicting findings have elucidated many questions about the origin and genetics of prehistoric dogs that have yet to be answered.

This topic is important due to its association with human evolution and migration. Human migratory patterns and gene flow can be understood by analyzing the population history and genomic sequencing of prehistoric dogs (Bergström et al. 2020). The researchers attempted to uncover when, where and how many times domestication of dogs occurred by analyzing data from prehistoric dogs and wolves. Overall, the findings of this paper are useful in examining migration and evolution holistically. Essentially, this is the question that future research can ask: what is a recurring population dynamic that resulted in dog migratory patterns resembling human ones? (Bergström et al. 2020). The research data from this article does not specifically answer this question but encourages future research to do so.

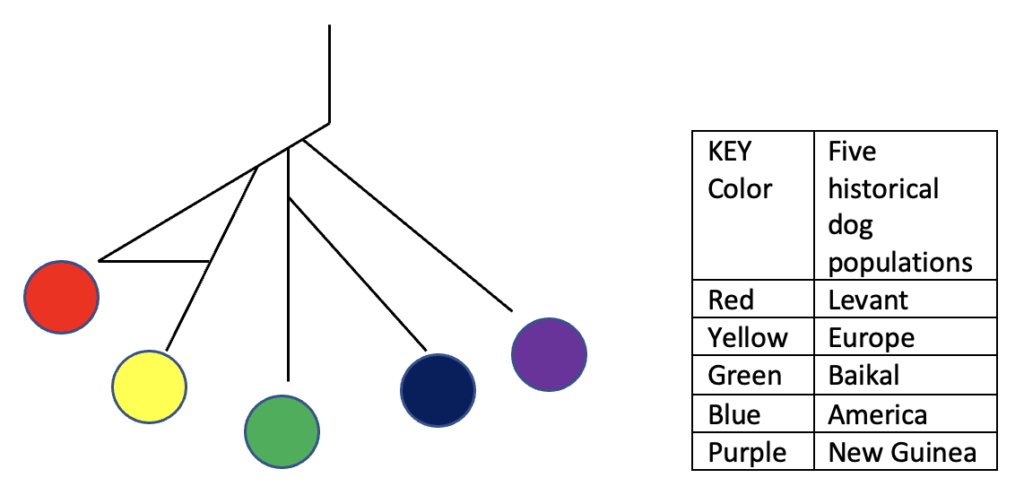

The authors of the research article “Origins and Genetic Legacy of Prehistoric Dogs” sequenced 27 prehistoric dog genomes to analyze its common ancestry with wolves and any gene flow that occurred. Further, the authors co-analyzed human genomes to suggest that the population histories of both species share a significant resemblance. To compare the 27 dog genomes to human genomes, the researchers used 17 sets of genome-wide data that mimicked the ages and locations of the dogs. Once this had all been collected, different comparisons and graphic data for the genetic relationships could be constructed. Computational analyses shed light on the genetic drifts and gene flow occurring within dog and wolf populations and further showed migratory patterns for dog populations (Fig. 2). One specific technique for analyses that was used is the principal component analysis or PCA. This compares groups by using intentionally ambiguous x-axis and y-axis variables to observe differences and similarities.

Research suggested that a previous interpretation of a dual origin for domesticated dogs is incorrect and that all dogs originated from a single point in time, likely from a singular wolf population (Bergström et al. 2020). This finding is important because while it doesn’t shed light on when dogs originated, it does specify that it was during one point in time. Further, research showed that only dogs contained DNA from wolves, but wolves had no DNA from dogs. This finding is significant because its geographic signal was strongest in Europe and East Asia (Bergström et al. 2020). This corroborates with the findings from the two conflicting studies that identified Europe and East Asia as the origin for domesticated dogs. While it is unclear which geographic origin is right, we can confirm it is one of these two regions. Further, the researchers analyzed the implications of this data on human population histories and deduced that both species shared overall features with each other.

This paper along with the four supplementary research papers explore genomic data on prehistoric dogs to shed light on their evolutionary and migration pattern. The paper I focused on is especially important because it was most recently published and, as such, has implications on some of the contradictory findings. While the geographic origin of domesticated dogs is unclear, it can be narrowed down to either Europe or East Asia and there seems to be one temporal origin not a dual temporal origin. However, there is still no data suggesting when that time occurred and no further data to fully conclude one geographic starting point (Bergström et al. 2020). It is clear that this is a subject that needs more research and the data collected is significant in further understanding human population history since the two species histories are associated. Further, the inferences made suggest the need for future research that focuses on how species evolutionary and migratory patterns share a recurring population dynamic that causes a resemblance of population histories.

Khlopachev G, Sablin M. 2002 The Earliest Ice Age Dogs: Evidence from Eliseevichi Ii. Current Anthropology Vol 43, No 5 : 795-797. doi: 10.1086/344372.

Savolainen P, Ya-ping Z, Luo J, Lundeberg J, Leitner T 2002 Genetic Evidence for an East Asian Origin of Domestic Dogs. Science 298 : 1610-1613. doi: 10.1126/science.1073906

Thalmann O, Shapiro B, Cui P, Schuenemann V.J., Sawyer S.K., et al. 2013 Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs. Science 342 : 871-874. doi: 10.1126/science.1243650

Frantz L, Mullin V, Pionnier-Capitan M, Lebrasseur O, Ollivier M, et al. 2016 Genomic and archaeological evidence suggest a dual origin of domestic dogs. Science 03 : 1228-1231. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3161

Bergström A, Frantz L, Schmidt R, Ersmark E, Lebrasseur O, et al. 2020 Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs. Science 370 : 557-564. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9572.

© Copyright 2021 Department of Biology, Davidson College, Davidson, NC 28036