As mice age, there is an increase in variability in the effectiveness of wound healing and cellular reprogramming.

This web page was produced as an assignment for an undergraduate course at Davidson College.

Age associated chronic inflammation is the unresolved and uncontrollable inflammation that worsens with old age. This type of inflammation carries on at a low-grade manner, which leads to build up with increasing age1. An unbalanced diet and smoking can speed along the process1; however, low-grade inflammation is inevitable for everyone at a certain point. Aged individuals consistently have higher levels of inflammatory cells compared to younger individuals. These inflammatory cells are called cytokines, where are immune system cells that help send signals throughout the body. A paper by Mahmoudi et al. looks at how age associated chronic inflammation affects wound healing and cellular reprogramming in mice.

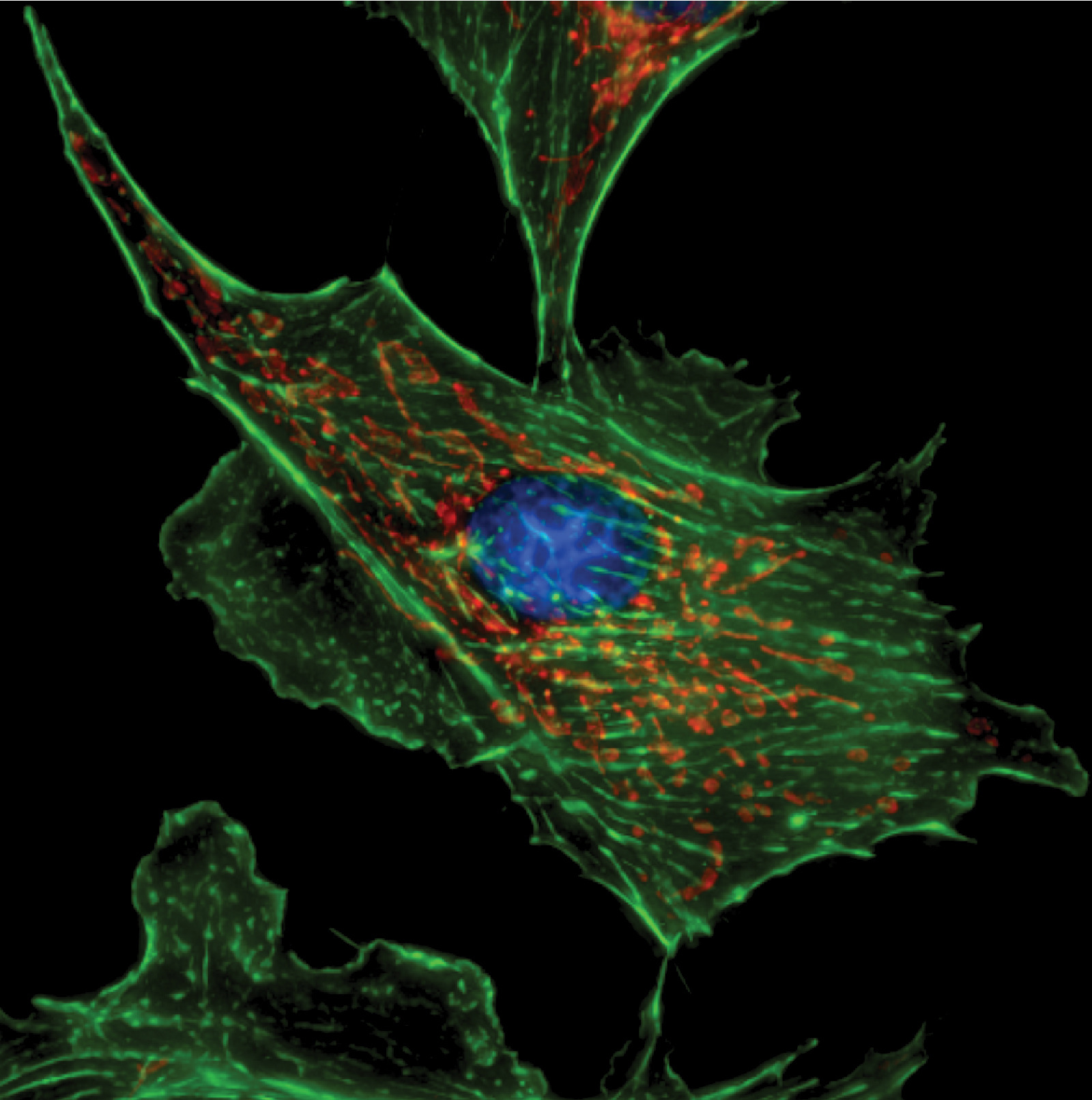

The cells in the body that contribute to wound healing are called fibroblasts. Fibroblasts are found in most tissues in the body and play a central role in the process of cell proliferation and differentiation that leads to this chronic inflammation2.

Reprogramming is the process in which a cell loses its identity and is programmed to have a new identity with a new function. The specific reprogramming mentioned in this paper is iPS reprogramming3, which involves the reprogramming of adult cells to a pluripotent stem cell4. Fibroblasts have the ability to reprogram to pluripotent stem cells and from there can give rise to several different cell types.

The authors carried out a series of experiments to help understand more about patterns of wound healing and reprogramming and how age influences these processes. Fibroblast cultures from old mice (aged 28-29 months) and young mice (aged 3 months) were collected in order to measure the levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Fibroblast cultures from old mice showed increased levels of immune systems cells that increase and regulate inflammation within the body.

Similarly, the researchers looked at fibroblast cultures of middle-aged and old mice to test whether age had an effect on the rate of cellular reprogramming. The researchers artificially induced reprogramming in the fibroblast cells. There was not a difference in the average level of efficiency in cellular reprogramming between the two age groups of mice. However, they did observe a highly variable rate of efficiency in the old mice cultures compared to the middle-aged mice. Meaning that some old mice fibroblast cultures seemed to reprogram very well, compared to other cultures that were less efficient.

The researchers noticed that reprogramming efficiency seemed to rely on the culture that the fibroblast cells came from, which shows efficiency is inherent to each individual mouse. Cultures were consistent in their programming efficiency, and after further analysis the older fibroblast cells showed enrichment of multiple transcriptional pathways compared to young fibroblasts. The enriched transcriptional pathways were pathways that are normally only “on” in activated fibroblasts. An activated fibroblasts differs from a senescent fibroblast such that it is giving off signals to induce inflammation and wound healing. In a properly regulated immune response these activated fibroblasts help with tissue repair.

The researchers then went on to look into how these activated fibroblasts contributed to reprogramming efficiency. Through a series of experiments, the researchers discovered the proportion of activated and non-activated fibroblasts in a culture determined how efficient the culture was at reprogramming. Activated fibroblasts secrete inflammatory cells that regulate inflammation within the body. Therefore, a higher proportion of activated fibroblasts also leads to an increase in wound healing in these older mice.

The major conclusion from this research is the variable number of activated and nonactivated fibroblasts in old mice plays a role in how efficient the cells are at reprogramming and wound healing. Therefore, the answer to how age influences wound healing and reprogramming in cells isn’t a simple answer. The variable nature of these processes that was observed means that each body handles wound healing and reprogramming at a different rate.

After this paper, the researchers still do not have a clear answer as to how this variability is so prominent in old age. Also, when does this variability start? Deficient and excessive wound healing are both issues that people in old age face, therefore understanding this large variability throughout the course of life could be important in helping to equalize wound healing to a sufficient rate.

These next questions are important to answer, but might also be difficult. Studies like this one use cultures to look at cells or even animal models, but usually the observed changes do not smoothly translate to how healing happens in the human body. Moreover, older adults tend to be excluded from randomized clinical trials due to the high probability of multi-morbidity; medicine regimes that could interfere with results; and increased vulnerability to stress5. These factors all play a role in the lack of human studies that have been done on wound healing in relation to old age.

References

1. Sanada, F. et al. Source of Chronic Inflammation in Aging. Front Cardiovasc Med 5, (2018).

2. Fibroblast. Genome.gov https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Fibroblast.

3. Takahashi, K. Cellular Reprogramming. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6, (2014).

4. Induced pluripotent stem cells – Latest research and news | Nature. https://www.nature.com/subjects/induced-pluripotent-stem-cells.

5. Gould, L. et al. Chronic Wound Repair and Healing in Older Adults: Current Status and Future Research. J Am Geriatr Soc 63, 427–438 (2015).